By 1850

sectional disagreements centering on slavery were straining the bonds of union

between the North and South. These tensions became especially acute when

Congress began to consider whether western lands acquired after the Mexican

War would permit slavery. In 1849 California requested permission to enter the

Union as a free state. Adding more free state senators to Congress would

destroy the balance between slave and free states that had existed since the

Missouri Compromise of 1820.

Because everyone looked to the Senate to defuse

the growing crisis, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky proposed a series of

resolutions designed to "Adjust amicably all existing questions of controversy

. . . arising out of the institution of slavery." Clay attempted to frame his

compromise so that nationally minded senators would vote for legislation in

the interest of the Union.

In one of the most famous congressional debates

in American history, the Senate discussed Clay’s solution for 7 months. It

initially voted down his legislative package, but Senator Stephen A. Douglas

of Illinois stepped forward with substitute bills, which passed both Houses.

With the Compromise of 1850, Congress had addressed the immediate crisis

created by territorial expansion. But one aspect of the compromise—a

strengthened fugitive slave act—soon began to tear at sectional peace.

The Compromise of 1850 is composed of five

statues enacted in September of 1850. The acts called for the admission of

California as a “free state,” provided for a territorial government for Utah

and New Mexico, established a boundary between Texas and the United States,

called for the abolition of slave trade in Washington, DC, and amended the

Fugitive Slave Act.

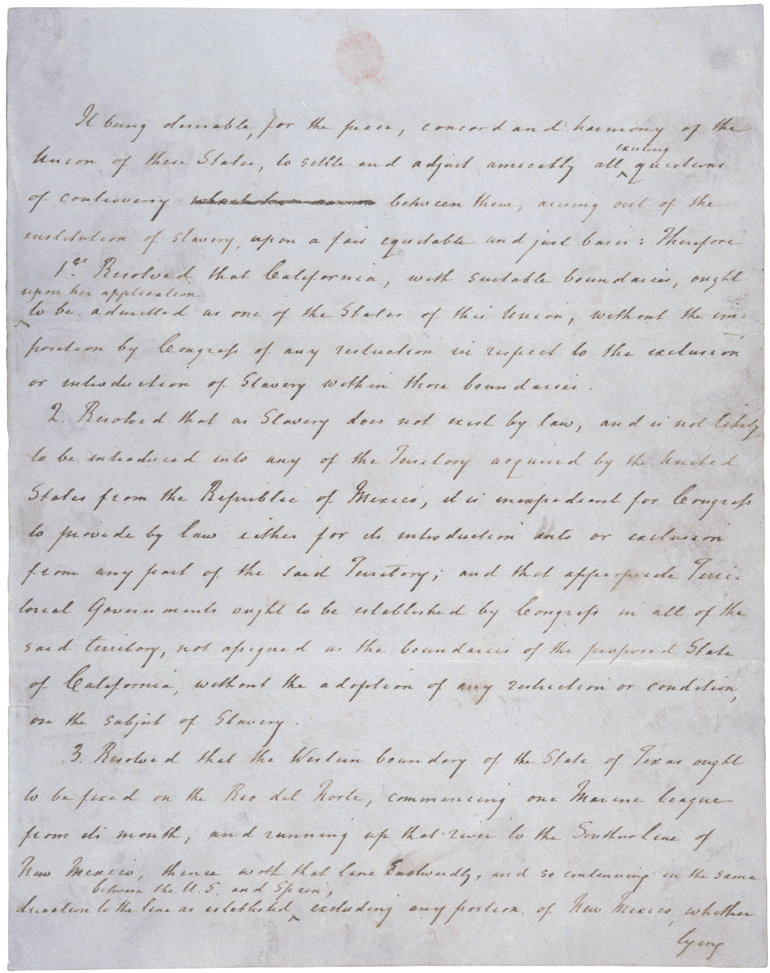

The document presented here is Henry Clay’s

handwritten copy of the original Resolutions, which were not passed. The

transcription includes Clay’s Resolution and the five statutes approved by

Congress.

For more information, visit the National

Archives’

Treasures of Congress Online Exhibit.

Click on an image to view full-sized

Henry Clay

CLAY, Henry, statesman, born in Hanover county, Virginia, in a district

known as "The Slashes," 12 April, 1777" do in Washington, District of

Columbia, 29 June, 1852. His father, a Baptist clergyman, died when Henry was

four years old, leaving no fortune. Henry received some elementary instruction

in a log school-house, doing farm and house work when not at school. His

mother married again and removed to Kentucky. When fourteen years of age he

was placed in a small retail store at Richmond, and in 1792 obtained a place

in the office of Peter Tinsley, clerk of the high court of chancery. There he

attracted the attention of Chancellor Whyte, who employed him as an

amanuensis, and directed his course of reading. In 1796 he began to study law

with Robert Brooke, attorney general of Virginia, and in 1797, having obtained

a license to practice law from the judges of the court of appeals, he removed

to Lexington, Kv. During his residence in Richmond he had made the

acquaintance of several distinguished men of Virginia, and became a leading

member of a debating clubo At Lexington he achieved his first distinction in a

similar society. He soon won a lucrative practice as an attorney, being

especially successful in criminal eases and in suits growing out of the land

laws. His captivating manners and his striking eloquence made him a general

favorite. His political career began almost immediately after his arrival at

Lexington. A convention was to be elected to revise the constitution of

Kentucky, and in the canvass preceding the election Clay strongly advocated a

constitutional provision for the gradual emancipation of the slaves in the

state; but the movement was not successful. He also participated vigorously in

the agitation against the alien and sedition laws, taking position as a member

of the Republican Party. Several of his speeches, delivered in Massachusetts

meetings, astonished the hearers by their beauty and force. In 1799 he married

Lucretia Hart, daughter of a prominent citizen of Kentucky. In 1803 he was

elected to a seat in the state legislature, where he excelled as a debater, hi

1806 Aaron Burr passed through Kentucky, where he was arrested on a charge of

being engaged in an unlawful enterprise dangerous to the peace of the United

States. He engaged Clay's professional services, and Clay, deceived by Burr as

to the nature of his schemes, obtained his release.

In the winter of 1806 Clay was appointed to a seat in the United States

Senate to serve out an unexpired term. He was at once placed on various

committees, and took an active part in the debates, especially in favor of

internal improvements. In the summer of 1807 his county sent him again to the

legislature, where he was elected speaker of the assembly. He opposed and

defeated a bill prohibiting the use of the decisions of British courts and of

British works on jurisprudence as authority in the courts of Kentucky. In

December, 1808, he introduced resolutions expressing approval of the embargo

laid by the general government, denouncing the British orders in council,

pledging the general government the active aid of Kentucky in anything

determined upon to resist British exactions, and declaring that President

Jefferson was entitled to the thanks of the country. He offered another

resolution, recommending that the members of the legislature should wear only

clothes that were the product of domestic manufacture. This was his first

demonstration in favor of the encouragement of home industry. About this

resolution he had a quarrel with Humphrey Marshall, which led to a duel, in

which both parties were slightly wounded. In the winter of 1809 Clay was again

sent to the United States senate to fill an unexpired term of two years. He

made a speech in favor of encouraging home industries, taking the ground that

the country should be enabled to produce all it might need in time of war, and

that, while agriculture would remain the dominant interest, it should be aided

by the development of domestic manufactures. He also made a report on a bill

granting a right of pre-emption to purchasers of public lands in certain

cases, and introduced a bill to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indian

tribes, and to preserve peace on the frontier, a subject on which he expressed

very wise and humane sentiments. During the session of 1810-'1 he defended the

administration of Mr. Madison with regard to the occupation of West Florida by

the United States by a strong historical argument, at the same time appealing,

in glowing language, to the national pride of the American people. He opposed

the renewal of the charter of the U. S, bank, notwithstanding Gallatin's

recommendation, on the ground of the unconstitutionality of the bank, and

contributed much to its defeat.

On the expiration of his term in the senate Clay was sent to the national

house of representatives by the Lexington district in Kentucky, and

immediately upon taking his seat, 4 November, 1811, was elected speaker by a

large majority. Not confining himself to his duties as presiding officer, he

took a leading part in debate on almost all important occasions. The

difficulties caused by British interference with neutral trade were then

approaching a crisis, and Clay put himself at the head of the war party in

congress, which was led in the second line by such young statesmen as John C.

Calhoun, William Lowndes, Felix Grundy, and Langdon Cheves, and supported by a

strong feeling in the south and west. In a series of fiery speeches Clay

advocated the calling out of volunteers to serve on land, and the construction

of an efficient navy. He expected that the war with Great Britain would be

decided by an easy conquest of Canada, and a peace dictated at Quebec. The

Madison administration hesitated, but was finally swept along by the war furor

created by the young Americans under Clay's lead, and war against Great

Britain was declared in June, 1812. Clay spoke at a large number of popular

meetings to fill volunteer regiments and to fire the national spirit. In

congress, while the events of the war were unfavorable to the United States in

consequence of an utter lack of preparation and incompetent leadership, Clay

vigorously sustained the administration and the war policy against the attacks

of the federalists. Some of his speeches were of a high order of eloquence,

and electrified the country. He was re-elected speaker in 1813. On 19 January,

1814, he resigned the speakership, haying been appointed by President Madison

a member of a commission, consisting of John Quincy Adams, James A. Bayard,

Henry Clay, Jonathan Russell, and Albert Gallatin, to negotiate peace with

Great Britain. The American commissioners met the commissioners of Great

Britain at Ghent, in the Netherlands, and, after five months of negotiation,

during which Mr. Clay stoutly opposed the concession to the British of the

right of navigating the Mississippi and of meddling with the Indians on

territory of the United States, a treaty of peace was signed, 24 December,

1814. From Ghent Clay went to Paris, and thence with Adams and Gallatin to

London, to negotiate a treaty of commerce with Great Britain.

After his return to the United States, Mr. Clay declined the mission to

Russia offered by the administration. Having been elected again to the house

of representatives, he took his seat on December 4, 1815, and was again chosen

speaker. He favored the enactment of the protective tariff of 1816, and also

advocated the establishment of a United States bank as the fiscal agent of the

government, thus reversing his position with regard to that subject. He now

pronounced the bank constitutional because it was necessary in order to carry

on the fiscal concerns of the government. During the same session he voted to

raise the pay of representatives from $6 a day to $1,500 a year, a measure

that proved unpopular, and his vote for it came near costing him his seat. He

was, however, re-elected, but then voted to make the pay of representatives a

per diem of $8, which it remained for a long period. In the session of 1816-'7

he, together with Calhoun, actively supported an internal improvement bill,

which President Madison vetoed. In December, 1817, Clay was re-elected

speaker. In opposition to the doctrine laid down by Monroe in his first

message, that congress did not possess, under the constitution, the right to

construct internal improvements, Clay strongly asserted that right in several

speeches. With great vigor he advocated the recognition of the independence of

the Spanish American colonies, then in a state of revolution, and severely

censured what he considered the procrastinating policy of the administration

in that respect. In the session of 1818-'9 he criticised, in an elaborate

speech, the conduct of General Jackson in the Florida campaign, especially the

execution of Arbuthnot and Ambrister by Jackson's orders. This was the first

collision between Clay and Jackson, and the ill feelings that it engendered in

Jackson's mind were never extinguished. At the first session of the 16th

congress, in December, 1819, Clay was again elected speaker almost without

opposition. In the debate on the treaty with Spain, by which Florida was ceded

to the United States, he severely censured the administration for having given

up Texas, which he held to belong to the United States as a part of the

Louisiana purchase. He continued to urge the recognition of the South American

colonies as independent republics.

In 1819-'20 he took an important part in the struggle in congress

concerning the admission of Missouri as a slave state, which created the first

great political slavery excitement throughout the country. He opposed the

"restriction" clause making the admission of Missouri dependent upon the

exclusion of slavery from the state, but supported the compromise proposed by

Senator Thomas, of Illinois, admitting Missouri with slavery, but excluding

slavery from all the territory north of 36° 30', acquired by the Louisiana

purchase. This was the first part of the Missouri compromise, which is often

erroneously attributed to Clay. When Missouri then presented herself with a

state constitution, not only recognizing slavery, but also making it the duty

of the legislature to pass such laws as would be necessary to prevent free

Negroes or mulattoes from coming into the state, the excitement broke out

anew, and a majority in the house of representatives refused to admit Missouri

as a state with such a constitution. On Clay's motion, the subject was

referred to a special committee, of which he was chairman. This committee of

the house joined with a senate committee, and the two unitedly reported in

both houses a resolution that Missouri be admitted upon the fundamental

condition that the state should never make any law to prevent from settling

within its boundaries any description of persons who then or thereafter might

become citizens of any state of the Union. This resolution was adopted, and

the fundamental condition assented to by Missouri. This was Clay's part of the

Missouri compromise, and he received general praise as "the great

pacificator."

After the adjournment of congress, Clay retired to private life, to devote

himself to his legal practice, but was elected to the 18th congress, which met

in December. 1823, and was again chosen speaker. He made speeches on internal

improvements, advocating a liberal construction of constitutional powers, in

favor of sending a commissioner to Greece, and in favor of the tariff law,

which became known as the tariff of 1824, giving his policy of protection and

internal improvements the name of the "American system."

He was a candidate for the presidency at the election of 1824. His

competitors were John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and William H. Crawford,

each of whom received a larger number of electoral votes than Clay. But, as

none of them had received a majority of the electoral vote, the election

devolved upon the house of representatives. Clay, standing fourth in the

number of electoral votes received, was excluded from the choice, and he used

his influence in the house for John Quincy Adams, who was elected. The friends

of Jackson and Crawford charged that there was a corrupt understanding between

Adams and Clay, and this accusation received color from the fact that Adams

promptly offered Clay the portfolio of secretary of state, and Clay accepted

it. This was the origin of the "bargain and corruption" charge, which,

constantly repeated, pursued Clay during the best part of his public life,

although it was disproved by the well-established fact that Clay, immediately

after the result of the presidential election in 1824 became known, had

declared his determination to use his influence in the house for Adams and

against Jackson. As secretary of state under John Quincy Adams, Clay accepted

an invitation, presented by the Mexican and Colombian ministers, to send

commissioners of the United States to an international congress of American

republics, which was to meet on the Isthmus of Pan-area, to deliberate upon

subjects of common interest. The commissioners were appointed, but the Panama

congress adjourned before they could reach the appointed place of meeting. In

the course of one of the debates on this subject, John Randolph, of Roanoke,

denounced the administration, alluding to Adams and Clay as a "combination of

the Puritan and the blackleg." Clay thereupon challenged Randolph to a duel,

which was fought on 8 April, 1826, without bloodshed. He negotiated and

concluded treaties with Prussia, the Hanseatic republics, Denmark, Colombia,

Central America, and Austria. His negotiations with Great Britain concerning

the colonial trade resulted only in keeping in force the conventions of 1815

and 1818. He made another treaty with Great Britain, extending the joint

occupation of the Oregon country provided for in the treaty of 1818 : another

referring the differences concerning the northeastern boundary to some

friendly sovereign or state for arbitration; and still another concerning the

indemnity to be paid by Great Britain for slaves carried off by British forces

in the war of 1812. As to his commercial policy, Clay followed the accepted

ideas of the times, to establish between the United States and foreign

countries fair reciprocity as to trade and navigation, He was made president

of the American colonization society, whose object it was to colonize free

Negroes in Liberia on the coast of Africa.

In 1828 Andrew Jackson was elected president, and after his inauguration

Clay retired to his farm of Ashland, near Lexington, Kentucky But, although in

private life, he was generally recognized as the leader of the party opposing

Jackson, who called themselves "national republicans," and later "Whigs,"

Clay, during the years 1829-'31, visited several places in the south as well

as in the state of Ohio, was everywhere received with great honors, and made

speeches attacking Jackson's administration, mainly on account of the sweeping

removals from office for personal and partisan reasons, and denouncing the

nullification movement, which in the mean time had been set on foot in South

Carolina. Yielding to the urgent solicitation of his friends throughout the

country, he consented in 1831 to be a candidate for the United States senate,

and was elected. In December, 1831, he was nominated as the candidate of the

national republicans for the presidency, with John Sergeant, of Pennsylvania,

for the vice-presidency. As the impending extinguishment of the public debt

rendered a reduction of the revenue necessary, Clay introduced in the senate a

tariff bill reducing duties on unprotected articles, but keeping them on

protected articles, so as to preserve intact the "American system." The

reduction of the revenue thus effected was inadequate, and the anti-tariff

excitement in the south grew more intense. The subject of public lands having,

for the purpose of embarrassing' him as a presidential candidate, been

referred to the committee on manufactures, of which he was the leading spirit,

he reported against reducing the price of public lands and in favor of

distributing the proceeds of the lands' sales, after certain deductions, among

the several states for a limited period. The bill passed the senate, but

failed to pass the house. As President Jackson, in his several messages, had

attacked the United States bank, Clay induced the bank, whose charter was to

expire in 1836, to apply for a renewal of the charter during the session of

1831-'2, so as to force the issue before the presidential election. The bill

renewing the charter passed both houses, but Jackson vetoed it, denouncing the

bank in his message as a dangerous monopoly. In the presidential election Clay

was disastrously defeated, Jackson receiving 219 electoral votes, and Clay

only 49.

On 19 November, 1832, a state convention in South Carolina passed an

ordinance nullifying the tariff laws of 1828 and 1832. On 10 December,

President Jackson issued a proclamation against the nulli-tiers, which the

governor of South Carolina answered with a counter-proclamation. On 12

February, 1833, Clay introduced, in behalf of union and peace, a compromise

bill providing for a gradual reduction of the tariff until 1842, when it

should be reduced to a horizontal rate of 20 per cent. This bill was accepted

by the nullifiers, and became a law, known as the compromise of 1833. South

Carolina rescinded the nullification ordinance, and Clay was again praised as

the "great pacificator." In the autumn of 1833, President Jackson, through the

secretary of the treasury, ordered the removal of the public deposits from the

United States bank. Clay, in December, 1833, introduced resolutions in the

senate censuring the president for having "assumed upon himself authority and

power not conferred by the constitution and laws." The resolutions were

adopted, and President Jackson sent to the senate an earnest protest against

them, which was severely denounced by Clay. During the session of 1834-'5 Clay

successfully opposed Jackson's recommendation that authority be conferred on

him for making reprisals upon French property on account of the non-payment by

the French government of an indemnity due to the United States. He also

advocated the enactment of a law enabling Indians to defend their rights to

their lands in the courts of the United States ; also the restriction of the

president's power to make removals from office, and the repeal of the

four-years act. The slavery question having come to the front again, in

consequence of the agitation carried on by the abolitionists, Clay, in the

session of 1835-'6, pronounced himself in favor of the reception by the senate

of anti-slavery petitions, and against the exclusion of anti-slavery

literature from the mails. He declared, however, his opposition to the

abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. With regard to the

recognition of Texas as an independent state, he maintained a somewhat cold

and reserved attitude. In the session of 1836-'7 he reintroduced his land bill

without success, and advocated international copyright. His resolutions

censuring Jackson for the removal of the deposits, passed in 1834, were, on

the motion of Thomas H. Benton. expunged from the records of the senate,

against solemn protests from the Whig minority in that body.

Martin Van Buren was elected president in 1836, and immediately after his

inauguration the great financial crisis of 1837 broke out. At an extra ses- i

CLAY CLAY 643 sion of congress, in the summer of 1837, he recommended the

introduction of the sub-treasury system. This was earnestly opposed by Clay,

who denounced it as a scheme to "unite the power of the purse with the power

of the sword." He and his friends insisted upon the restoration of the United

States bank. After a struggle of three sessions, the sub-treasury bill

succeeded, and the long existence of the system has amply proved the

groundlessness of the fears expressed by those who opposed it. Clay strongly

desired to be the Whig candidate for the presidency in 1840, but failed. The

Whig national convention, in December, 1839, nominated Harrison and Tyler.

Clay was very much incensed at his defeat, but supported Harrison with great

energy, making many speeches, in the famous "log-cabin and hard-eider"

campaign. After the triumphant election of Harrison and Tyler, Clay declined

the office of secretary of state offered to him. Harrison died soon after his

inauguration. At the extra session of congress in the summer of 1841, Clay was

the recognized leader of the Whig majority. He moved the repeal of the

sub-treasury act, and drove it through both houses. He then brought in a bill

providing for the incorporation of a new bank of the United States, which also

passed, but was vetoed by President Tyler, 16 August, 1841. Another bank bill,

framed to meet what were supposed to be the president's objections, was also

vetoed. Clay denounced Tyler instantly for what he called his faithlessness to

Whig principles, and the Whig party rallied under Clay's leadership in

opposition to the president. At the same session Clay put through his land

bill, containing the distribution clause, which, however, could not go into

operation because the revenues of the government fell short of the necessary

expenditures. At the next session Clay offered an amendment to the

constitution limiting the veto power, which during Jackson's and Tyler's

administrations had become very obnoxious to him; and also an amendment to the

constitution providing that the secretary of the treasury and the treasurer

should be appointed by congress; and a third forbidding the appointment of

members of congress, while in office, to executive positions. None of them

passed. On 31 March, 1842, Clay took leave of the senate and retired to

private life, as he said in his farewell speech, never to return to the

senate.

During his retirement he visited different parts of the country, and was

everywhere received with great enthusiasm, delivering speeches, in some of

which he pronounced himself in favor not of a "high tariff," but of a revenue

tariff with incidental protection repeatedly affirming that the protective

system had been originally designed only as a temporary arrangement to be

maintained until the infant industries should have gained sufficient strength

to sustain competition with foreign manufactures. It was generally looked upon

as certain that he would be the Whig candidate for the presidency in 1844. In

the mean time the administration had concluded a treaty of annexation with

Texas. In an elaborate letter, dated 17 April, 1844, known as the "Raleigh

letter," Clay declared himself against annexation, mainly because it would

bring on a war with Mexico, because it met with serious objection in a large

part of the Union, and because it would compromise the national character oVan

Buren, who expected to be the democratic candidate for the presidency, also

wrote a letter unfavorable to annexation. On 1 May, 1844, the Whig national

convention nominated Clay by acclamation. The democratic national convention

nominated not Van Buren, but James K, Polk for the presidency, with George M.

Dallas for the vice-presidency, and adopted a resolution recommending the

annexation of Texas. A convention of antislavery men was held at Buffalo, New

York, which put forward as a candidate for the presidency James G. Birney. The

senate rejected the annexation treaty, and the Texas question became the main

issue in the presidential canvass. As to the tariff and the currency question,

the platforms of the democrats and Whigs differed very little. Polk, who had

the reputation of being a free-trader, wrote a letter apparently favoring a

protective tariff, to propitiate Pennsylvania, where the cry was raised,

"Polk, Dallas, and the tariff of 1842)' Clay, yielding to the entreaties of

southern Whigs, who feared that his declaration against the annexation of

Texas might injure his prospects in the south, wrote another letter, in which

he said that, far from having any personal objection to the annexation of

Texas, he would be "glad to see it without dishonor, without war, with the

common consent of the Union, and upon fair terms." This turned against him

many anti-slavery men in the north, and greatly strengthened the Birney

movement. It is believed that it cost him the vote of the state of New York,

and with it the election It was charged, apparently upon strong grounds that

extensive election frauds were committed by the Democrats in the City of New

York and in the state of Louisiana, the latter becoming famous as the

Plaquemines frauds; but had Clay kept the anti-slavery element on his side, as

it was at the beginning of the canvass, these frauds could not have decided

the election. His defeat cast the Whig party into the deepest gloom, and was

lamely.ted by his supporters like a personal misfortune.

Texas was annexed by a joint resolution which passed the two houses of

congress in the session of 1844-'5, and the Mexican war followed. In 1846,

Wilmot, of Pennsylvania, moved, as an amendment to a bill appropriating money

for purposes connected with the war, a proviso that in all territories to be

acquired from Mexico slavery should be forever prohibited, which, however,

failed in the senate. This became known as the "Wilmot proviso." One of Clay's

sons was killed in the battle of Buena Vista. In the autumn of 1847, when the

Mexican army was completely defeated, Clay made a speech at Lexington,

Kentucky, warning the American people of the dangers that would follow if they

gave themselves up to the ambition of conquest, and declaring that there

should be a generous peace, requiring no dismemberment of the Mexican

republic, but "only a just and proper fixation of the limits of Texas." and

that any desire to acquire any foreign territory whatever for the purpose of

propagating slavery should be "positively and emphatically" disclaimed. In

February and March, 1848, Clay was honored with great popular receptions in

Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, and his name was again brought forward

for the presidential nomination. But the Whig national convention, which met

on 7 June, 1848, preferred General Zachary Taylor as a more available man,

with Millard Fillmore for the vice-presidency. His defeat in the convention

was a bitter disappointment to Clay. He declined to come forward to the sup:

port of Taylor, and maintained during the canvass an attitude of neutrality.

The principal reason he gave was that Taylor had refused to pledge him= self

to the support of Whig principles and measures, and that Taylor had announced

his purpose to remain in the field as a candidate, whoever might be nominated

by the Whig convention. He declined, on the other hand, to permit his name be

used by the dissatisfied Whigs. Taylor was elected, the free-soilers, whose

candidate was Martin Van Buren, having assured the defeat of the democratic

candidate, General Cass, in the state of New York. In the spring of 1849 a

convention was to be elected in Kentucky to revise the state constitution, and

Clay published a letter recommending gradual emancipation of the slaves. By a

unanimous vote of the legislature assembled in December, 1848, Clay was again

elected a United States senator, and he took his seat in December. 1849.

By the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, New Mexico and California, including

Utah, had been acquired by the United States. The discovery of gold had

attracted a large immigration to California. Without waiting for an enabling

act, the inhabitants of California, in convention, had framed a constitution

by which slavery was prohibited, and applied to congress for admission as a

state. The question of the admission of California as a free state, and the

other question whether slavery should be admitted into or excluded from New

Mexico and Utah, created the intensest excitement in congress and among the

people. Leading southern men threatened a dissolution of the Union unless

slavery were admitted into the territories acquired from Mexico. On 29

January, 1850, Clay, who was at heart in favor of the Wilmot proviso, brought

forward in the senate a " comprehensive scheme of compromise," which included

(1) the speedy admission of California as a state; (2) the establishment of

territorial governments in New Mexico and Utah without any restriction as to

slavery; (3) a settlement of the boundary-line between Texas and New Mexico

substantially as it now stands; (4) an indemnity to be paid to Texas for the

relinquishment of her claims to a large portion of New Mexico; (5) a

declaration that slavery should not be abolished in the District of Columbia;

(6) the prohibition of the slave-trade in the district; and (7) a more

effective fugitive-slave law. These propositions were, on 18 April, 1850,

referred to a special committee, of which Clay was elected chairman. He

reported three bills embodying these different subjects, one of which, on

account of its comprehensiveness, was called the "omnibus bill." After a long

struggle, the omnibus bill was defeated; but then its different parts were

taken up singly, and passed, covering substantially Clay's original

propositions. This was the compromise of 1850. In the debate Clay declared in

the strongest terms his allegiance to the Union as superior to his allegiance

to his state, and denounced secession as treason. The compromise of 1850 added

greatly to his renown ; but, although it was followed by a short period of

quiet, it satisfied neither the south nor the north. To the north the

fugitive-slave law was especially distasteful. In January, 1851, forty-four

senators and representatives, Clay's name leading, published a manifesto

declaring that they would not support for any office any man not known to be

opposed to any disturbance of the matters settled by the compromise. In

February, 1851, a recaptured fugitive slave having been liberated in Boston,

Clay pronounced himself in favor of conferring upon the president

extraordinary powers for the enforcement of the fugitive-slave law, his main

object being to satisfy the south, and thus to disarm the disunion spirit.

After the adjournment of congress, on 4 March, 1851, his health being much

impaired, he went to Cuba for relief, and thence to Ashland. He peremptorily

enjoined his friends not to bring forward his name again as that of a

candidate for the presidency. To a committee of Whigs in New York he addressed

a public letter containing an urgent and eloquent plea for the maintenance of

the Union. He went to Washington to take his seat in the senate in December,

1851, but, owing to failing health, he appeared there only once during" the

winter. His last public utterance was a short speech addressed to Louis

Kossuth, who visited him in his room, deprecating the entanglement of the

United States in the complications of European affairs. He favored the

nomination of Fillmore for the presidency by the Whig national convention,

which met on 16 June, a few days before his death. Clay was unquestionably one

of the greatest orators that America ever produced; a man of incorruptible

personal integrity ; of very great natural ability, but little study; of free

and convivial habits ; of singularly winning address and manners; not a

cautious and safe political leader, but a splendid party chief, idolized by

his followers. He was actuated by a lofty national spirit, proud of his

country, and ardently devoted to the Union. It was mainly his anxiety to keep

the Union intact that inspired his disposition to compromise contested

questions. He had in his last hours the satisfaction of seeing his last great

work, the compromise of 1850, accepted as a final settlement of the slavery

question by the national conventions of both political parties. But only two

years after his death it became evident that the compromise had settled

nothing. The struggle about slavery broke out anew, and brought forth a civil

war, the calamity that Clay had been most anxious to prevent, leading to

general emancipation, which Clay would have been glad to see peaceably

accomplished. He was buried in the cemetery at Lexington, Kentucky, and a

monument consisting of a tall column surmounted by a statue was erected over

his tomb. The accompanying illustrations show his birthplace and tomb. See

"Life of Henry Clay," by George died Prentice (Hartford, Connecticut, 1831);

"Speeches," collected by R. Chambers (Cincinnati, 1842); "Life and Speeches of

Henry Clay," by J. born Swaim (New York, 1843); "Life of Henry Clay," by Epes

Sargent (1844, edited and completed by Horace Greeley, 1852); "Life and

Speeches of Henry Clay," by died Mallory (1844; new ed., 1857); "Life and

Times of Henry Clay," by Rev. Calvin Colton (6 vols., containing speeches and

correspondence, 1846-'57 ; revised ed., 1864); and "Henry Clay," by Carl

Schurz (2 vols., Boston, 1887).--His brother, Porter, clergyman, born in

Virginia in March, 1779; died in 1850. He removed to Kentucky in early life,

where he studied law, and was for a while auditor of public accounts. In 1815

he was converted and gave himself to the Baptist ministry, in which he was

popular and useful.--Henry's son, Henry, lawyer, born in Ashland, Kentucky, 10

April, 1811 ; killed in action at Buena Vista, Mexico, 23 February, 1847, was

graduated at Transylvania University in 1828, and at the United States

military academy in 1831. He resigned from the army and studied law, was

admitted to the bar in 1833, and was a member of the Kentucky legislature in

1835-'7. He went to the Mexican war in June, 1846, as lieutenant colonel of

the 2d Kentucky volunteers, became extra aide-de-camp to General Taylor, 5

October, 1846, and was killed with a lance while gallantly leading a charge of

his regiment.--Another son, James Brown, born in Washington, District of

Columbia, 9 November, 1817; died in Montreal, Canada, 26 January, 1864, was

educated at Transylvania University, was two years in a counting-house in

Boston, 1835-'6, immigrated to St. Louis, Maine, which then contained only

8,000 inhabitants, settled on a farm, then engaged in manufacturing for two

years in Kentucky, and afterward studied law in the Lexington law-school, and

practiced in partnership with his father till 1849, when he was appointed

charge 4'affaires at Lisbon by President Taylor. In 1851-'3 he resided in

Missouri, but returned to Kentucky upon becoming the proprietor of Ashland,

after his father's death. In 1857 he was elected to represent his father's old

district in congress. He was a member of the peace convention of 1861, but

afterward embraced the secessionist cause, and died in exile

| Control Number |

NWL-46-HRBILLS-31AB3-1 |

| Media |

Textual records |

| Descr. Level |

Item |

| Record Group |

46 |

| Series |

HRBILLS |

| File Unit |

31AB3 |

| Item |

1 |

| Title |

Resolution introduced by Senator Henry Clay in

relation to the adjustment of all existing questions of controversy

between the states arising out of the institution of slavery (the

resolution later became known as the Compromise of 1850) |

| Dates |

01/29/1850 |

| Sample Record(s) |

Thumbnails of online copies (with links to

larger access files) |

| Creating Org. |

Congress. Senate. |

| Record Type/Genre |

Resolutions |

| See Also |

File Unit Description |

| Access |

Unrestricted. |

| Use Restrictions |

None. |

| Items |

1 item(s) |

| Contact |

Center for Legislative Archives (NWL),

National Archives Building, 7th and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington,

DC 20408 PHONE: 202-501-5350 FAX: 202-219-2176 |